English version is here.

※「8/14は、みんなで一日中、打ち水」は雨天のため延期になりました。詳しくはこちらをご覧ください。

今年の三大ミッションの一つ、「8/14は、みんなで一日中、打ち水」。

この8月14日は、旧暦(太陰太陽暦)では、2021年の「七夕」の日にあたります。

現在の暦では、7月7日が「七夕」とされていますから、この旧暦の七夕は、「伝統的七夕」の名称で呼ばれることもあります。

七夕と言えば、7月7日の夜に、星を祭る年中行事です。

「織り姫(おりひめ)」と「彦星(ひこぼし)」が年に一度だけ、会うことができる日。

短冊にお願いごとをする日。

空を見上げ、星を眺めるロマンティックな日のはずですが、

雨だったり、曇っていたり、ということが結構多いのではないでしょうか。

それもそのはず。考えてみれば、7月7日は、梅雨の真っただ中。

日本が現在の暦を使うようになったのは、今から約150年前の1873年(明治6年)から。

それまでは、古代より旧暦に基づいて、「七夕」が行われていたはずです。

旧暦の七夕(7月7日)の日は、今の暦で変換すると、ほぼ8月となります(年によって日は変わります)。ですから、梅雨が明けた夏の真っただ中に、七夕が行われていたことになります。

さて、かつて日本には、旧暦の七夕の日に行われる、興味深い習慣がありました。

それは、各所で使われている井戸を、みんなでそれぞれいっせいに掃除する1、というものです。

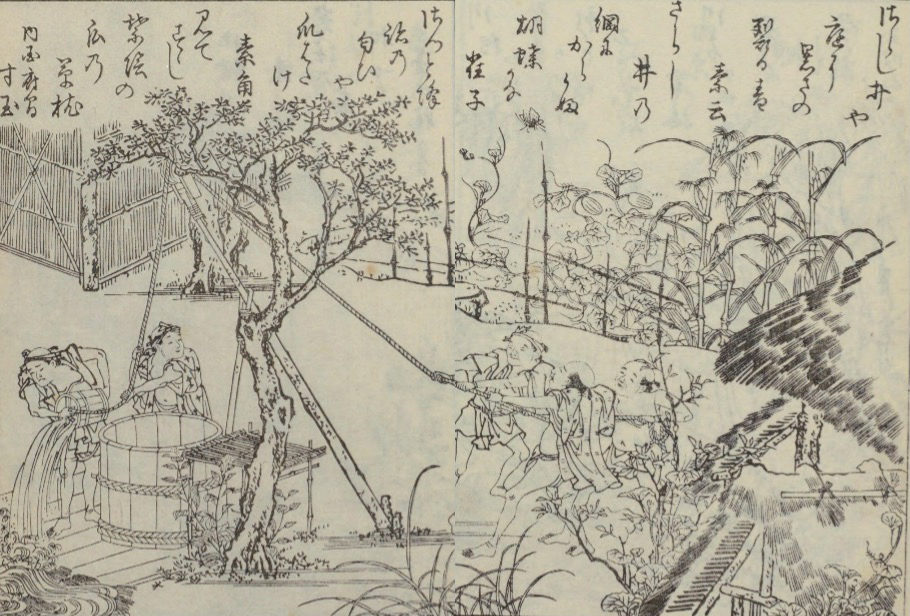

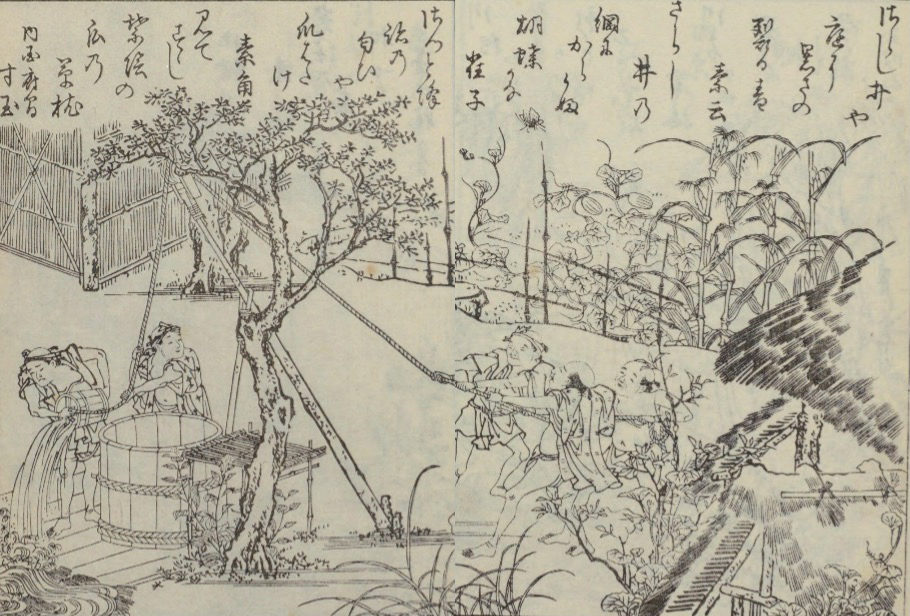

江戸の町の、この七夕の井戸掃除の様子が様々な文献2に描かれています。

ちなみに、当時、江戸の人々が使っていた井戸は、地下水をくみ上げるタイプではなく、「上水井戸」が主流でした。すなわち、江戸の町では、早くも、多摩川などを原水とする水道網が地下に張り巡らされており、各所の井戸がその水道水を溜め、くみ上げる場所になっていました。

つまり、町中の井戸は、地下で繋がっていたわけです。みんなでいっせいに掃除するのは、極めて効果的な方法であったと考えられます。

出典:黒川真道 編「日本風俗図絵第10輯」(国立国会図書館書誌データを基に作成)

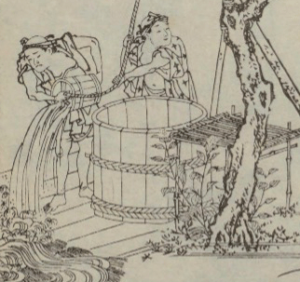

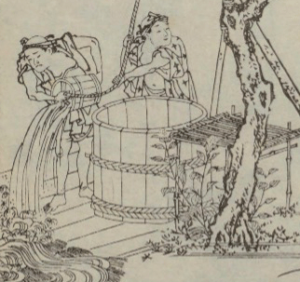

これは、「日本風俗図絵」に描かれた、江戸の井戸掃除の日の一コマです。

左下に、井戸を空にするために、水を汲み出している様子が見てとれます。

こんなことをするわけですから、雨の日には、なかなか難しい作業のはずです。

はたして、この日が「晴れ」ることがわかっていたのでしょうか。

私は、ここで衝撃の事実を目の当たりにしました。

実は、旧暦の七夕の日は、結構な確率で「晴れ」ているようなのです。

気象庁のデータ3で、過去50年間の「東京」観測地点の「伝統的七夕」の日を確認してみると、日合計「0.0mm」 4を超える降水を観測したのは、10日のみ。80%の確率で、少なくともまとまった雨は観測されていないことになります。

「福岡」「大阪」「札幌」観測地点でのデータもほぼ同様の傾向でした。

(近年の方が、より晴れる傾向にありました。札幌はやや雨が多いようです。)

絵に戻ります。

左下の方は、井戸から汲み出した水を流し続けているようです。

なるほど、昔から、この日は「いっせい打ち水」の日でもあったのかもしれません。

令和の打ち水大作戦は、過去の歴史に目を向けながら、打ち水の意味や意義を再確認していきます。

晴れると言われる「伝統的七夕」の日。培われてきた人々の叡智と、昨今の気候の変化にも思いをはせながら、ぜひこの日を迎えてください。もし本当に晴れたら、打ち水してみるのもよろしいのではないでしょうか。

最後に、上記「日本風俗図絵」井戸掃除の挿絵に書き込まれた俳句をご紹介します5。

・さらし井や 庭から暑さの 裂る音(素云)

・さらし井の 綱にからかふ 胡蝶かな(雀子)

・さつと浚 洗の匂ひや 瓜をさけ(素角)

打ち水に似た情景が浮かび上がってはいないでしょうか。

打ち水大作戦本部 浅井重範(家元)

1井戸浚え、井戸替え、晒井(さらしい)などと呼ばれた。「晒井」は夏の季語とされている。

2菊池貴一郎 (芦乃葉散人) 著「絵本江戸風俗往来」など

3気象庁「過去の気象データ検索」https://www.data.jma.go.jp/obd/stats/etrn/

40.5mm未満を含む。気象台等においては、「0.0mm」は降水はあったが0.5mmに達しなかったものを表す。

5文献からそのまま読み取っております。誤りがございましたら大変申し訳ございません。

参考:

・国立天文台「質問3-9)七夕について教えて」「質問3-10)伝統的七夕について教えて」

・高橋達郎「年に一度、江戸中の井戸をお掃除する。」クリナップ(江戸散策)

・江戸monoStyle「江戸時代の7月7日に行われた「井戸替え」とは?」

・夢見る獏(バク)「井戸浚い(江戸の祭礼と歳事)」気ままに江戸♪散歩・味・読書の記録

・東京都水道歴史館「東京水道の歴史」

・かわうそ@暦「新暦・旧暦変換」

The Secret of August 14th, 2021

(Due to expected severe weather conditions, the date of "Uchimizu throughout the day on August 14th" was postponed to August 23rd. For more details, please visit here.)

As one of the three main missions of Mission Uchimizu 2021, we call on people to practice uchimizu (sprinkle water) at home or in other places where they are, as often as possible throughout the day on August 14th. This year, August 14th coincides with the day of Tanabata, the Star Festival, according to the lunar calendar. In the today’s Gregorian calendar, Tanabata falls on July 7th. The day of Tanabata in the lunar calendar is referred to as the “Traditional Tanabata”.

Tanabata is known as the Star Festival because, according to a legend, that is the only night of the year when two stars, Vega (known as weaving princess) and Altair (known as herdsman), can meet after traveling across the Milky Way galaxy. On that day, people write their wishes on pieces of colored papers and hang them on broadleaf bamboos. Though it is supposed to be a romantic night when people look up at the sky to see the shining stars, it has often been rainy or cloudy that evening on July 7th in the Gregorian calendar. This is because that day is in the middle of the rainy season in Japan.

Japan started using the Gregorian calendar in 1873, about 150 years ago. Until then, the Tanabata festival had been held according to the lunar calendar. July 7th in the lunar calendar fell around August in today’s Gregorian calendar (the date varies depending on the year). This meant that Tanabata was celebrated in the middle of summer after the rainy season in old times.

In Japan, there used to be a unique custom practiced on the day of traditional Tanabata. People worked together to clean their wells on that day1.

There are documents2 left that show how the people of Edo (Tokyo) cleaned their wells. Most wells in Edo were not used to draw water from the aquifers but connected to networks of underground wooden pipes and stored water supplied through the networks from water sources such as the Tama river. In short, the wells across the city of Edo were connected to each other underground. Therefore, it was reasonable and effective for people to work together to clean their wells on the same day.

Source: The 10th edition of Nippon Fuuzoku Zue, compiled by Kurokawa Mamichi, The National Diet Library bibliographic data.

This picture from the book Nippon Fuuzoku Zue (Encyclopedia of Japanese annual events: woodblock prints of the Edo period) shows the scene of Ido Sarae. Local residents are drawing out of water from the well before cleaning.

It must have been difficult to do such a job on a rainy day. I wonder how the people of Edo knew that the day would be sunny.

I've found some eye-opening facts about the weather on that day. When I checked data from the Japan Meteorological Agency3 collected over the past 50 years at the Tokyo District Meteorological Observatory, I found that only ten of the traditional Tanabata days saw rainfall exceeding 0.0 millimeters4. Almost 80 percent of the days saw no significant rainfall.

The data recorded at the other district meteorological observatories in Fukuoka, Osaka, and Sapporo showed similar results. (Please note in particular that recent traditional Tanabata days have a tendency of being a sunny. However, Sapporo received a little more rain than other locations.)

Getting back to the picture, people in the lower left seem to be drawing water from the well and pouring it on the ground. Looking at this scene, it occurred to me that Tanabata might have been also a day for people to practice uchimizu together.

During Mission Uchimizu in the current Reiwa period, we will keep in mind the meaning and importance of uchimizu by remembering the past history and old customs.

I hope you will enjoy the day of traditional Tanabata while thinking about the people’s wisdom accumulated through the history and the change of climate in recent years. If the day is indeed sunny, shall we practice uchimizu together?

Last but not least, I would like to present some haiku poems5 about cleaning well described in Nippon Fuuzoku Zue.

・Sarashi-i ya Niwa kara Atsusa no Sakuru Oto(by Soun)

(A day for cleaning the well The sound of water from the garden Brings relief from the heat)

・Sarashi-i no Tsuna ni Karakau Kochou kana(by Jakushi)

(While we clean the well A butterfly is flying playfully Around the well rope)

・Satto Sarai Sen no Nioi ya Uri wo Sake(by Sokaku)

(The well has been cleaned A cool fresh current from pouring waterSwiftly flows around a melon)

I hope these haiku poems inspire you to imagine a similar scene of uchimizu.

1This custom was called “Ido-sarae”, “Ido-kae” or “Sarashi-i”. Sarashi-i is a term symbolizing summer in Haiku poems.

2Example: Kikuchi, Kiichiro (Ashinoha, Sanjin). Ehon Edo Fuuzoku Oorai.

3Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) (2021). Kako no Kishou-deeta Kensaku (Search of past meteorological data), JMA website, accessed 2 August 2021. https://www.data.jma.go.jp/obd/stats/etrn/

4Rainfall of 0.0 millimeters includes rainfall less than 0.5 millimeters, according to the Meteorological Observatories.

5Original texts were written by using old characters. I apologize for any errors.

Reference:

・1) The National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ). FAQ: Q.3-9) and Q.3-10), NAOJ website, accessed 2 August 2021. https://www.nao.ac.jp/faq/

2) Takahashi, Tatsuro. Nen ni Ichido Edojuu no Ido wo Osouji Suru (Cleaning wells all over the city of Edo), Cleanup website, accessed 2 August 2021. https://cleanup.jp/life/edo/51.shtml

3) Edo monoStyle (2017). Edo-jidai no Shichigatsu Nanoka ni Okonawareta Ido Gae towa? (What is Ido Gae conducted on July 7th in the Edo period?), Edo monoStyle blog, accessed 2 August 2021. https://www.edomono.jp/blog/2017/07/02/

4) Yumemiru Baku (2015). Ido Sara-i (Cleaning wells) (A festival and annual event in the Edo period), Blog, accessed 2 August. https://wheatbaku.exblog.jp/24378594/

5) Tokyo Waterworks Historical Museum (TWHM). Toukyou Suidou no Rekishi (The history of Tokyo waterworks), TWHM website, accessed 2 August. https://www.suidorekishi.jp/pdf/s_history.pdf

6) Kawauso @ Koyomi. Shinreki Kyuureki Henkan (Conversion of the lunar and Gregorian calendar), Koyomi no Peiji, accessed 2 August. http://koyomi.vis.ne.jp/directjp.cgi?http://koyomi.vis.ne.jp/kyuureki.htm